“Who Invented School?”: A History of Classroom Education

The idea of school – grouping students together in a location for the purposes of leaning – has existed for thousands of years. Ancient Greece considered education in a gymnasium essential to childhood development. Ancient Rome was famed for its tuition-based system. Even Ancient India had the gurukul system of education where students would live, study and work near a guru. Modern “school”, however, is considered to be invented by Horace Mann, the Secretary of Education in Massachusetts, at the beginning of the 19th century.

This article will answer that age-old question: “Who invented school?” We’ll take you through the beginnings of formal education in Ancient Greece, Rome, India and China – before covering education in the Middle Ages. Finally, you’ll learn about how the modern system of education was invented in the United States, beginning in Massachusetts and eventually spreading throughout the country.

Ancient School: Greece, Rome, India and China

Greece

The idea of school can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece. Here when boys from wealthy families reached the age of 16, they were sent to tertiary education to study philosophy and rhetoric. If you wanted to become influential and powerful, understanding rhetoric was essential. Knowing how to speak and capture an audience meant you could lead a political rally or make a name for yourself on a court, and also become a well-known name at informal drinking parties that were called symposia.

In the city-state of Ancient Sparta boys as young as 6 would leave their parents and take part in a state education system designed to instil discipline and obedience. At the age of 16, the boys joined an organization known as "krupteia," a military police force. They were then sent to live in the Messenia jungle, where they were required to survive on their own and intimidate the local population. Education in Ancient Sparta therefore emphasised strength, military training and leadership, training youths in the art of war.

Rome

There were no official ‘schools’ in Ancient Rome. Instead, families would employ tutors who would teach the students at home. The conditions of the teaching facilities would vary. While a tutor teaching a wealthy family would do so in comfort and with high-quality facilities, many other tutors would teach in less-than-ideal surroundings. The Roman historian Suetonius (69 to c. 130/140 CE) refers to the room he taught in as a pergola, a porch or courtyard. Some teachers with fewer resources would even have to hold tutoring sessions in outdoor public spaces such as streets or town squares.

As time progressed, education began to be done in larger groups. Quintilian (35-96 CE) believed that school was preferable to home education because of the social community that students had access to. So while some tutors (such as the poet Martial, c. 38/41 to c. 102/104 AD) had a maximum of 3 students, Quintilian tells us he had a ‘crowd’ in grammar and rhetorical schools.

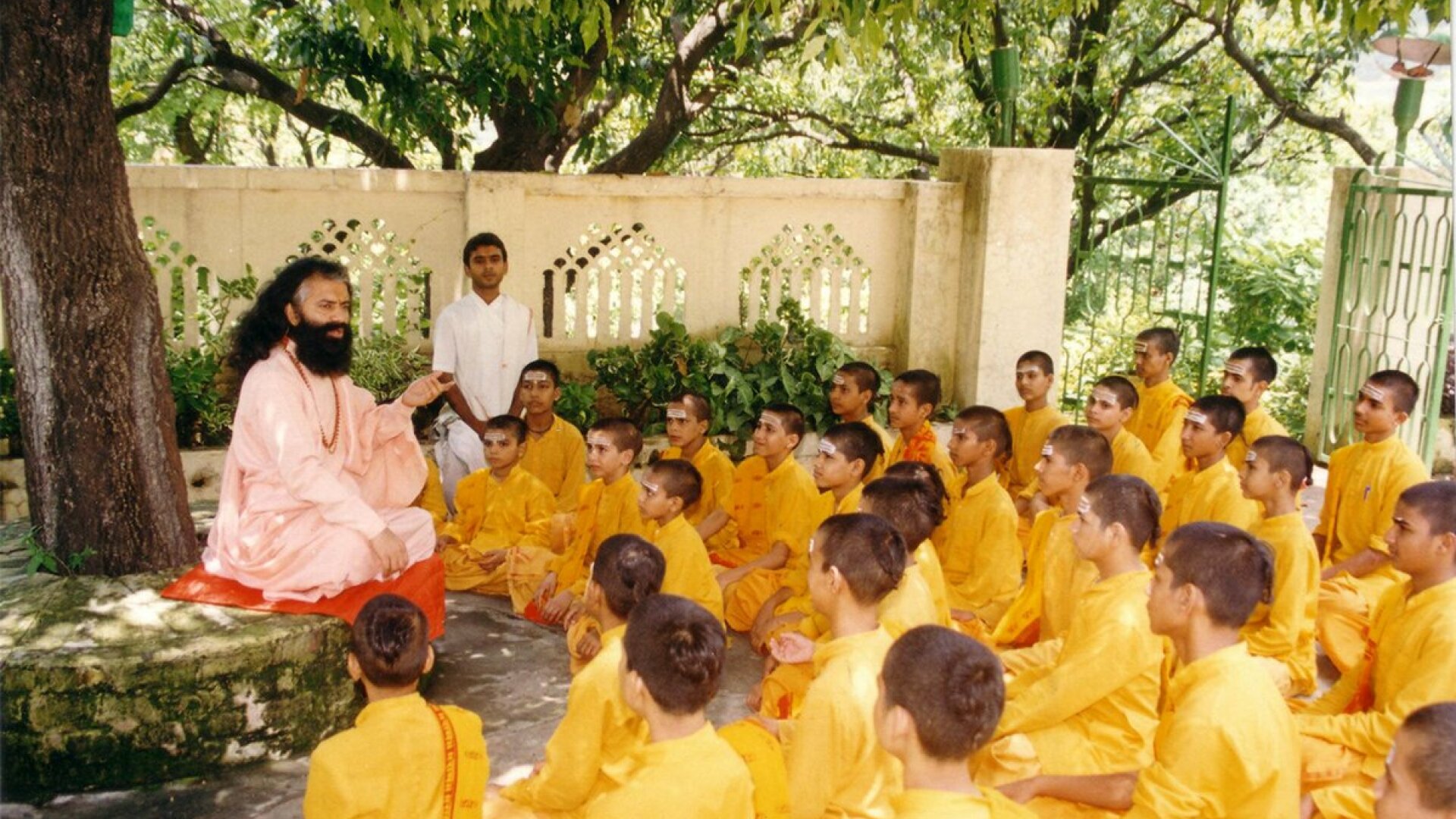

Ancient India

School in Ancient India centered around the figure of the guru. Children would leave their family and home in order to live with this guru in what was called a gurukul. This form of education didn’t demand any fees, it was completely free but dependant on one thing: physical labour. So while the guru would take care of everything, providing food, clothes, and shelter; the child would be expected to work on the land daily. This is how they ‘paid’ for their education.

Ancient India actually had two ‘systems’ of education, Vedic and Buddhist. Subjects covered in the Vedic system were ritualistic knowledge, metrics, grammar, phonetics and astronomy, along with history, logic and reasoning. In the Buddhist system, children would learn about law, performing arts, ethics, art, architecture and military science.

Ancient China

Ancient China had a surprisingly developed form of school education. The first schools were created as far back as the Xia dynasty (2070 BC-1600 BC). Here the schools were divided between those that took the children of the nobility and those where children of ordinary citizens studied. State schools were exclusively for the children of the nobility. These schools were made up of both elementary schools and higher-level colleges. On the other hand, village schools, which were also referred to as local schools, were categorized into four levels: shu, xiang, xu, and xiao. Generally, students who performed well in shu would progress up to xiang and so on. The most determined and persistent students would make it to xiao and, if they performed well, stood a chance at going to college.

Schools in the Middle Ages

School in medieval Europe was mostly run by the church. The goal of these monastic and cathedral schools was to train future clergy and monks. Learning was mainly focused on religious education, reading and writing Latin and studying scripture.

Students were taught the ability to memorize and interpret Bible passages, learn about the lives of saints, and understand theological concepts. Christian moral and ethical values were emphasized, with teachings on the sacraments, the Ten Commandments, and principles of Christian living.

While the majority of the education focused on Christian principles, students would also be exposed to arithmetic, writing, and grammar. Most of this was related to practical skills people needed to be part of society: arithmetic was mainly confined to basic calculations related to business and trade, while writing was crucial for communication, record-keeping, and creating religious documents.

Horace Mann and the Invention of School

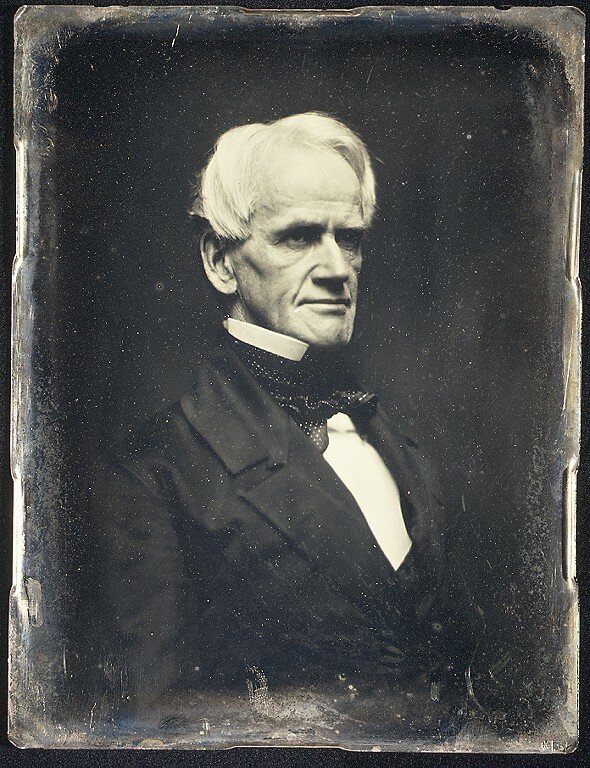

While medieval Europe and ancient civilizations had systems of education, these can’t really be considered ‘modern’ school. The person who is considered to have invented the concept of school is Horace Mann. Born in 1796, Mann was a pioneer of educational reforms in the US State of Massachusetts. After he became Secretary of Education in 1837, he undertook one of the biggest education reforms in American history.

While he was Secretary of Education, Mann went around the state holding teachers’ conventions, delivering lectures and introducing reforms. One of the key things Mann did was to persuade his fellow modernizers to create laws that supported tax-funded education in their states. These ‘Common Schools’, as they were known, were created to educate all children regardless of region or district – and because they were tax-funded, all children could attend them.

A big part of the success of these schools was the idea that all teachers had to have the same basic training. Teachers would have to attend ‘normal schools’ or teacher training colleges to learn how to teach. This meant, in theory, all teachers would have the same, standardized teacher training.

Mann's vision was to unite children from all social classes through education, creating a shared learning experience. He believed that education in common schools would help to bridge the gap between the less fortunate and the privileged, creating a more equal society.

Education Today

While much has changed since the days of Horace Mann, schools today still rely on the same ideas of standardized tests and taxpayer revenue that came from Horace’s era of common schools. What’s largely changed is the curriculum. Schools today teach innovative STEM and STEAM education programs that capture students' imagination through real-life technical education. These often rely on cutting-edge teaching and learning equipment that can give children a complete understanding of how theoretical knowledge can be translated into hands-on learning experiences.